Chapters In Books

Within the towering shelves of the Grand Archive, knowledge is rarely bound in isolation. Many of the greatest tomes of scholarship, magic, and history are not the work of a single mind but the collective wisdom of many. In such volumes, individual chapters hold unique insights, specialized theories, or forgotten truths, each a piece of a larger puzzle. Citing a chapter in a book is different from referencing an entire tome—it highlights a specific contribution within a broader collection. Whether written by a scholar within a grand historical chronicle, a mage refining a single school of magic, or a philosopher debating the nature of fate, a chapter citation ensures their voice is heard within the vast chorus of knowledge.

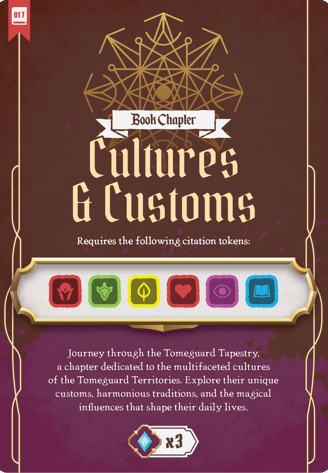

To properly cite a book chapter, one must include:

The chapter’s author, who contributed a distinct perspective to the work.

The book’s editor(s), who compiled and shaped the overarching text.

The chapter title, which identifies its unique focus within the broader work.

The full book details, ensuring that the chapter is situated within its proper scholarly context.

Even in a library as vast as the Grand Archive, individual voices should never be lost to time. Whether quoting a single revelation from a scholar of the arcane or extracting a hidden truth from an ancient chronicle, a chapter citation preserves the integrity of specialized knowledge within the grander whole.

Studies on Arcane Principles

Some scholars dedicate entire lifetimes to a single school of magic, yet their contributions are often woven into grander compilations of knowledge. Referencing these chapters ensures that individual breakthroughs are not lost in the vastness of the whole.

Example (Harvard Style): Brightwing, L. (Year 1125). “The Lunar Cycle’s Influence on Astral Conjurations.” In Starborn, E. (ed.) Celestial Thaumaturgy: Essays on Astral Magic. Celestial Quill Press, pp. 113-145.

Historical Accounts within Greater Chronicles

Not all historians pen entire tomes of their own—some add their voices to monumental works compiled over centuries. Their contributions provide vital clarity, first-hand accounts, or divergent interpretations of history’s grand events.

Example (APA 7th Edition): Shadowmere, T. (Year 1349). The Fall of the Starlit Kingdom: A Reckoning with Fate. In Moonwhisper, T. (Ed.), The Grand Histories of Etherea (pp. 221-265). Celestial Quill Press.

Philosophical Reflections in Compiled Wisdom

When sages and mystics gather to share their perspectives on existence, no single voice dominates—instead, each chapter offers a distinct path to enlightenment. To cite these, one must give credit to the individual philosopher and the collection’s guiding hand.

Example (Chicago Style): Eldrin, M. 1112. “The Nature of Time and the Fractured Reality.” In Lunaria, V., ed. Reflections Upon the Infinite: A Collection of Celestial Wisdom. Grand Library of Etherea.

Just as no single star defines a constellation, no book is complete without the sum of its parts. Citing chapters ensures that individual voices, forgotten theories, and hidden insights are brought into the light, giving proper recognition to those who contribute to greater tomes of wisdom. When referencing a single spark within a greater fire, remember—the smallest ember can ignite revolutions of thought.